Press

Filter Bubble and Echo Chamber. Information in the time of Social Networks

27 July 2021

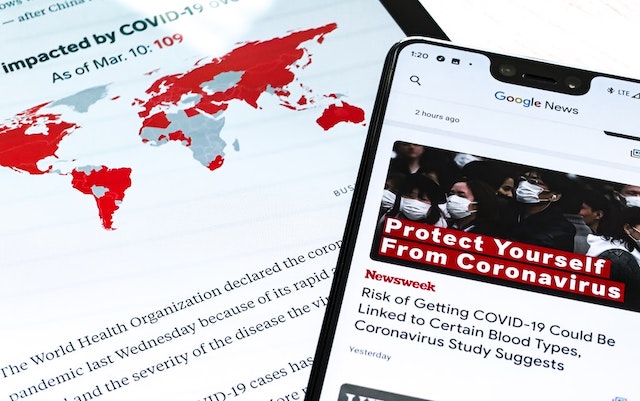

Information is changing. By now it is there for all to see: online news consumption is part of our daily lives, while the use of print sources appears to be increasingly declining.

In 2021, according to the Digital News Report compiled by the Reuters Institute, only 18 percent of people say they buy newspapers or daily papers on a weekly basis. There is also an exponential growth in the segment of the population that informs itself via social networks – Facebook, Instagram and Twitter in primis -, especially young people between the ages of 14 and 35.

In the face of this surge in the spread of social media as the only accredited channel of information, alarm bells inevitably ring.

We often speak of “disintermediation” to define the lack of that traditional media acting as a check on information according to precise professional rules. In the absence of proper monitoring of the new digital channels-provided by leading realities in the field-the spread of fake news, so-called “fake news,” is an inevitable consequence.

Filter bubble and echo chamber: what they are and how to recognize them

It is good to remember that any news that appears on social networks, on par with images, content and comments, is not random but filtered by algorithms. In fact, there are clearly identifiable mechanisms behind the infodemic-the spread of news that has become as viral as a pandemic-that grips our times, and it is good to recognize and clear them so as not to be a prisoner of them.

These are filter bubbles and echo chambers. These phenomena are in some ways very similar, but should not be confused.

The term “filter bubble” was coined by American scholar Eli Pariser, who in his book “Filter Bubble: What The Internet Is Hiding From You” (Penguin Group, 2011) defined personalized information ecosystems generated by algorithms by the same name. These algorithms, based on the user’s previously granted preferences, tend to propose content similar to what the user likes.

The filter bubble is thus a personalized space that shows us only what we want to see-which is why our social networks appear aligned with our interests. The algorithm stores our preferences and replays them to us in a continuous loop that is difficult to unhinge.

The so-called echo chamber, on the other hand, is a direct consequence of filter bubbles: a mechanism whereby we encounter only information consistent with our views, on any topic from fashion to sports to politics.

Reinforced by the filter bubble, the echo chamber is a closed system that is impervious to different ideas. Opinions, within the echo chamber, are thus reinforced by repetition

The comfort zone created by social networks

In practice, social networks create a user-tailored comfort zone: each of us lives in our own personal happy island, convinced that we are connected with a plurality of individuals and information, while in reality the algorithms keep re-proposing to us a narcissistic view of ourselves amplified in the reflection of others.

On social channels, content is proposed to us by assonance and similarity, reflecting the preferences granted by our “likes” and not the actual worldview. This seemingly harmless phenomenon can have risky consequences especially when associated with the intellectual and cultural sphere of individuals. If we do not read information that challenges our ideas we will consequently never be inclined to change them. Moreover, it is precisely filter bubbles and echo chambers that are the engines behind the rampant spread of the dreaded “fake news.”

Information in the age of Post-truth

In 2016, Oxford Dictionaries elected “Post-truth,” Post-truth, word of the year bringing to the forefront an issue that has been questioned for some time. We live in an age when the objectivity of facts has become of secondary importance in the face of their emotional impact or their implicit adherence to our beliefs.

Within echo chambers, therefore, erroneous beliefs can also be reinforced and new forms of consensus building formed as a result. This is exactly what happened with the Brexit in Britain and the election of Donald Trump in America. The phenomena have been analyzed by scholars, scientists and journalists who have placed a magnifying glass on “fake” posts and articles shared with a rebound effect on the social wall of millions of people.

“This is how election campaigns are built today,” noted journalist Carole Cadwalladr in the conclusion of a piece published in The Observer.

Recognizing echo chambers

So let us return to the starting point: social networks are an extraordinary information tool, but to be such they must be used with critical thinking and awareness.

It is not easy to realize that one is trapped in an echo chamber since this digital space leverages psychological mechanisms embedded in the individual’s mind. First and foremost is the “need to belong,” the need to be part of a group that characterizes all human beings and causes us to express opinions and judgments before a like-minded audience. Secondly, what scholars have termed “confirmation bias,” that need to gain each other’s approval and support for our ideas and stances.

The echo chamber banishes opinions contrary to our own, protects us from contact-clash with otherness that can be a cause of stress or fear: in fact, it gratifies us, which is precisely why it is difficult to become aware of the ideological trap in which we are caught.

Filter bubble: how to burst the filter bubble

Knowing how to consciously select information today, in the dizzyingly changing world of the Web, is crucial. The effect of filter bubbles and resulting echo chambers on online communication can be smoothed out, thus stemming that “misinformation” condition created by social algorithms.

While it is true that the mathematical intelligence of an algorithm is infallible, we must remember that as human beings we can make use of much more powerful weapons such as reflection, critical thinking, and dialogue.

For example, when faced with the latest news read on social media we might begin to ask ourselves some simple questions:

- Does it tend to give a single point of view on the issue?

- Is that viewpoint supported by facts or incomplete evidence?

- Is data that disagrees with the view expressed ignored or downplayed?

If the answer to each of these questions is yes, we are probably in the presence of an echo chamber or echo chamber. Getting out of the vicious circle of online information is actually much easier than we think: after all, all we need to do is to open our minds and start following pages and accounts that manifest different ideas, broaden our pool of sources even outside our favorite websites. By doing so, the algorithm behind the filter bubble will explode or, if nothing else, be quite confused by the renewed complexity of our interests.

The importance of media monitoring

The best example of media monitoring in Italy can be found in the modus operandi of L’Eco della Stampa, which has always recognized the value of knowledge and information. Sensing the central role played by the media in communication, it serves the national press as the first form of monitoring.

Over the years, the scope of L’Eco della Stampa has expanded to include new channels, from television to the Internet and contemporary social media. Today, L’Eco is the absolute leader in Italy among media monitoring services: in fact, it collects more news than its main competitors and guarantees an optimal service even to the smallest realities distributed throughout the territory, thanks to the strength of its team and the vocational professionalism that guides all employees.

How to escape the filter bubble effect?

Lastly, the importance of adequate digital literacy -to use social media properly by developing the ability to control and filter what is placed before our eyes every day from the scrolling homepages of our virtual accounts- should not be overlooked.

Finally, to escape the echo effect of social algorithms there always remains one surefire method: to step outside the restricted world of the net from time to time and converse with real, flesh-and-blood people, to open up to that wonderful and unpredictable discovery that is dialogue with the other.

Facebook and the fight against fake news

Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg himself has decided to adapt to the new vision of the network as a “tool for bringing people together.” Realizing the urgency of renewal, based on the fight against disinformation and greater communicative transparency, Zuckerberg chose the new name to give to his company: no longer Facebook, but Meta.

The term “Meta” is a contraction of a word of Greek origin to be understood as “metaverse.” According to fantasy author Neal Stephenson, the metaverse represents a parallel virtual reality, a kind of new world built by the individual avatars of users. Which is exactly what the creator of Facebook aspires to, which, through an investment of more than $150 million, intends to realize an innovative and inclusive communication model.

According to Mark Zuckerberg the metaverse is to be understood as:

“The metaverse will be the successor to the mobile Internet. We will be able to feel present as if we are right there with people, no matter how far away we are. We will be able to express ourselves in new joyful and fully immersive ways”.

Facebook then changed its name and became Meta. Zuckerberg’s move is neither random nor a simple renewal of image; the mind behind Facebook has moved strategically behind the scenes to checkmate fake news and echo chamber. Through the new name of Meta, Zuckerberg intends to move away from the problems related to the widespread disinformation that have poisoned Facebook in recent years.

Meta is a sign of a decisive turning point, of an epochal renewal: “We are not only a social media company, but in our DNA we are a company that uses technology to connect people. And the metaverse is the new frontier,” Zuckerberg said.

The mind behind The Social Network then returns to its initial purpose: “connect” and not “disunire”, declaring war on its enemy number one: the echo chamber effect.